It almost entirely reversed the blood-thinning action of unfractionated heparin and another form, low-molecular-weight heparin, more effectively than protamine in both cases. The DGL with a charge of +41 worked best. The researchers tested the idea by comparing DGLs of different sizes to protamine in their ability to halt heparin’s activity in plasma. Unfractionated heparin carries the highest negative charge, about -90, of any biomolecule, so the scientists figured their DGLs would have a hard time staying away from it. Each lysine holds one positive charge, so the DGL molecules they prepared varied from a one-branch version with a charge of +7 to their bushiest version at +727. DGL is a polymer made of lysine chains that looks like a hairy bush, with multiple branches sprouting off of one another. Vial, Gérald Monard of the University of Lorraine, Jean-Christophe Gris of the University Hospital of Nîmes, and their coworkers think they have an especially promising one: dendrigraft poly-L-lysine (DGL). “There is strong incentive to find a new, safe substitute for protamine,” Vial says.Ī handful of possible alternatives are now in preclinical and clinical stages. If bleeding ensues after administering synthetic heparin (fondaparinux), which doesn’t bind protamine at all, physicians have no antidote. And although protamine binds unfractionated heparin, the type used for surgeries, it doesn’t work as well against two other types of heparin, which are often used to treat deep vein thrombosis, when blood clots form in the legs. Worldwide supply is dependent on salmon availability. It is a mixture of small proteins isolated and purified from salmon sperm, and some patients have a severe allergic reaction or sudden low blood pressure in response to the drug. Protamine, however, is problematic, says Laurent Vial at University of Lyon. The reversal agent is given to about 2 million heart bypass patients per year. Once surgery is over, they inject protamine to bind up and inactivate heparin, restoring blood clotting. But too much blood thinning can lead to uncontrolled bleeding, so in the operating room, surgeons always keep protamine, the only heparin antidote approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, on hand.

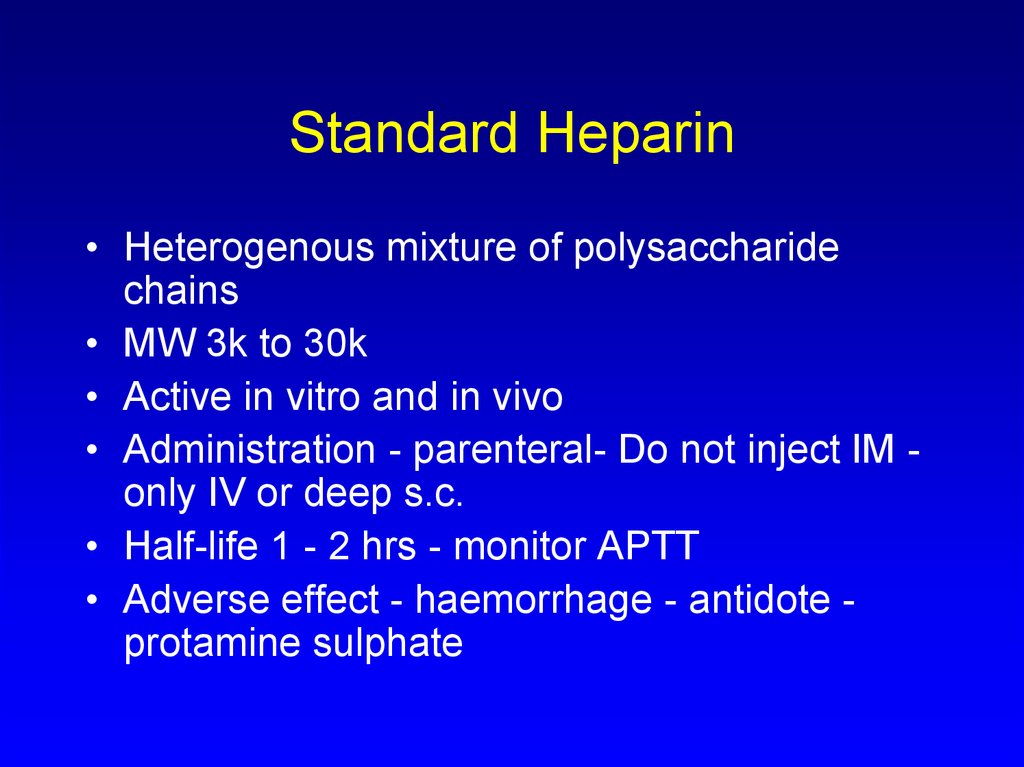

Heparin, a carbohydrate polymer of varying chain lengths, binds to the antithrombin III enzyme, halting the cascade of reactions that cause blood to clot. The polymer needs to be tested for toxicity and effectiveness in animals to see if it could lead to a long-sought-after, universal heparin antidote. Chemists have now developed a promising substitute: a branched, all-lysine polymer that binds all three commonly used forms of heparin in plasma. Protamine has several disadvantages, though, so doctors would like an alternative. But they also rely on protamine, which binds heparin and blocks its action, to restore clotting when needed.

Doctors rely on the drug heparin, a blood thinner, to prevent blood clots during surgery and kidney dialysis.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)